An introduction to reloading - Part 4

It is the case that you actually reload. Once you fire the cartrige, the bullet is gone, the primer has to be replaced. The shell, however, can and should be reused. Therefore, the quality of your cartridges is influenced not only by the quality of the brass you buy, but also by how you prepare it for the next round.

Repeatability is the key to success in reloading. "Unification" is a word that is repeated at every stage of work. Weighing the powder, seating the bullet at the right depth, taking care to maintain axiality, crimp control and many other activities translate into the final result. However, all efforts are doomed to failure if they are not preceded by care for the quality of the cases used.

Source of the brass

The importance of good quality brass cannot be emphasized enough. All other reloading components will be used just once. A bad bullet will have a negative impact on one shot. A poor case will remain and will affect each subsequent cartridge. Remember that you can use the case several times - if you buy a bad case from the start, you will struggle with it over and over again. And on the other hand, opting for the best cases possible is a fantastic starting point - you've got big variable out of the equation.

The cases used for reloading should come from one manufacturer (personally, I have never found better cases than those offered by NORMA), and preferably from the same batch. That's why, when I start reloading, I stock up on at least 50 new cases (for hunting purposes) and 200-300 (for sports). They should last a lifetime (mine or barrel).

Having cases from the same batch make a lot of sense, because after cleaning, sizing, trimming, etc., you get a consistent uniformity of the external shape. However, if the walls are of different thicknesses, despite your efforts, there will be different volumes inside. And this translates into differences in the pressure and velocity of the projectile, which will make it impossible to get a consistent performance out of the cartridges.

You can often find offers for sale of used cases - from private collections, shooting ranges, shooting cinemas, etc. Be careful. Used cases of unknown origin are the least valuable. They may come from different batches, they may have been used many times, and they may have been fired from weapons with different chamber sizes. Better to just avoid them.

Cleaning the case

The first thing to do with a fired case is thorough cleaning. Removing the remains of the previous use is important, because dirt can hinder the correct assessment of the condition of the case and its sizing, contribute to the wear of the dies, cause extraction difficulties etc. Above all, however, polished, shiny cases please the eye and testify to the attitude of the reloader to his hobby. It is difficult to expect good results if you make major compromises or neglect diligence from the very beginning.

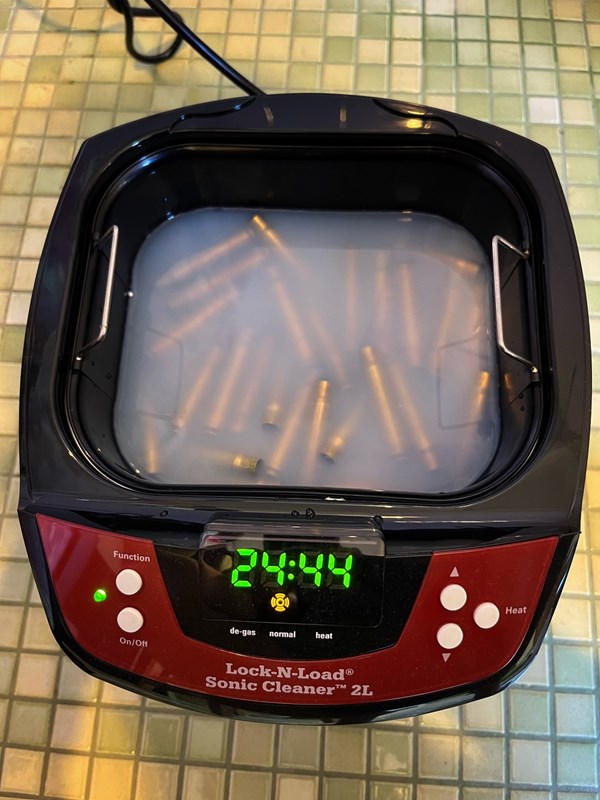

Dedicated cleaning devices are rotary or vibrating polishers, so-called tumblers. Cleaning is carried out wet, in the presence of a liquid that dissolves carbon deposits and steel shot or other polishing agent, or dry in a special granulate produced on the basis of e.g. nut cases. An alternative are ultrasonic baths, which clean quickly and thoroughly, but do not polish the surface of the brass, which remains somewhat dull after finishing (only aesthetically significant). When wet cleaning, always remember to dry the cases thoroughly. Moisture inside will make reloading a time consuming process of producing duds...

Quality control of the case

After cleaning the case, you must carefully inspect and eliminate from further use all that have deep deformations (except the mouth edge - this will be corrected during formatting) and any cracks. You should also check whether there is no narrowing inside the case near the bottom due to material defects or excessive headspace (the distance between the front of the bolt and the bottom of the case resting on the front part of the cartridge chamber). For inspection, you can use a piece of thin and stiff wire, curved at the end, which will allow you to feel a possible indentation. Of course, you can use a much more professional instrument, equipped with a dial indicator that allows you to measure the thickness of the case walls.

The importance of this stage increases with the number of reuses of a given batch of cases. Freshly purchased cases are usually good to go (quality again), but after the first shot there may be nasty surprises, especially if the chamber of the weapon has an unusual shape.

Sizing

Sizing can cover the case along its entire length, a standard die is used for this, usually marked with the letters FL (full length) or only selected sections: neck sizing, shoulders bumping or just the body (neck excluded). In most cases, full sizing is the simplest and completely sufficient solution. Special dies are used primarily in precision shooting, where it is desirable to perfectly match the case to the cartridge chamber.

Before using the dies, carefully read the manufacturer's instructions on how to position them in the press. My general practical note is to adjust the die so that the cases are sized only to the extent that allows for trouble-free loading of the gun. Rifles often differ in headspace, i.e. the distance from the bolt face to the arms of the cartridge. If the headspace is larger than the standard size, there is no need to size the case to the standard and then have it blown by the pressure again. It's just unnecessary fatigue of the brass material.

Don’t forget to lubricate the case before sizing - it prevents jamming in the die. The applied layer of oil or wax should be thin, a larger amount may cause deformation of the case in the die.

Trimming

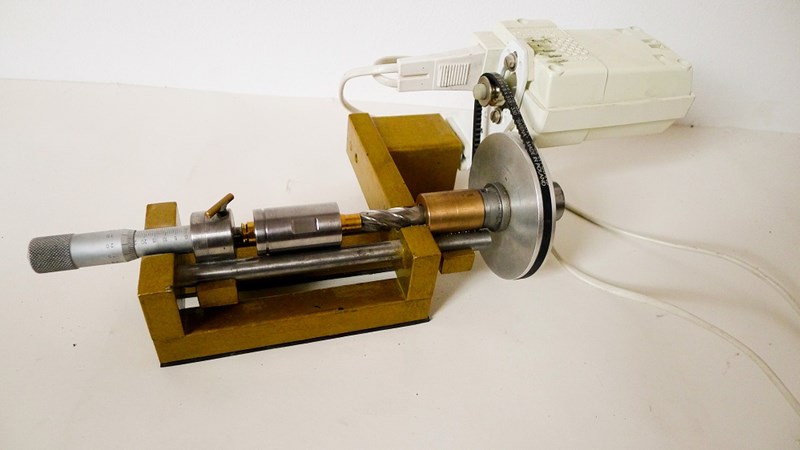

After sizing, it is worth unifying the length of the cases with a trimmer. Before proceeding with this operation, check in the manual for the appropriate length. If all of the brass does not exceed the max length, the trimmer should be set for the shortest case in the whole batch, so all other cases will be trimmed accordingly.

The shortened cases have sharp edges, so after trimming, carefully chamfer the mouth of each case with a chamfer tool and deburring.

Sorting

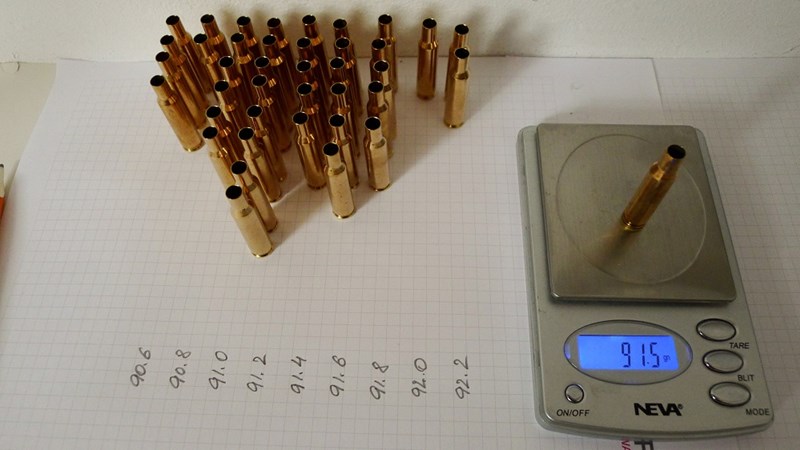

The last operation of the greatest importance in precision shooting is the final sorting. Usually it comes down to measuring the weight of the cases in order to eliminate those that differ from the others in the volume of the powder chamber. Of course, you can start weighing only when the outer dimensions of the cases are the same. Sorting will result in having a couple of perfectly uniform batches of cases ready for the next stage of meticulous handloading.

You could, of course, perform a volumetric sort (which excludes possible differences in the material). In such case, every case is weighed twice: first dry and then filled with water up to the edge of the neck (remember to close the primer socket, e.g. with an inverted shot primer). Calculation of the difference between the measurements will allow determining the volume of water in the case (often given in grains of H2O). This is quite a useful data for computer calculations, which I will devote a separate episode to.

Sorting – of any kind - is very time-consuming and it is done only when there is uncertainty as to the origin of the brass (different manufacturers, different batches). Let me repeat again - the quality of the cases we chose for reloading cannot be overestimated.

For precision shooting, it is worth dividing the cases into separate batches that do not differ in weight by more than 0.5%. But again, for hunting purposes one could argue, that sorting is not necessary. In the end, it all comes down to what we really need in the field.

There's more if you want to deep dive into the topic

There are some steps involved in the case preparation that have been deliberately omitted from the description above. These include, for example, neck turning and thermal tempering of cases. The first step is performed to unify or reduce the neck thickness in order to fit tight chambers in some models of competition guns. Tempering is performed because, as a result of repeated sizing, the material in the upper part of the case becomes increasingly hard, which leads to uneven clamping force as well as cracking of the neck or shoulders. However, it is worth remembering that in the early stages of the adventure with reloading, you should focus on the necessary activities. Reliable conduct of basic operations usually allows for very good results. Whether they can be noticeably improved by applying many additional activities is another topic for long discussions around the campfire.

Depriming before cleaning

A sonic cleaner with get the brass clean but not polished

Generally a rotary tumbler will require more engagement but will produce perfectly polished brass

The cases have to be lubricated before sizing

Additional dry lubrication for the inner side of the neck

Three sizing dies (L to R): a body die, neck sizing die (here with a bushing) and full length sizing die

Sizing requires some force - a heavy press and possibly even mounting the bench to the floor helps

A DIY trimmer for cutting the brass to the required length

Some final chamfering

Weight sorting for best results