Effective Game Killing

Effective Game Killing

Introduction

We are living in a society where most of the World’s population now live in cities. Food is harvested, packaged and delivered to those who live in the city. As the global population becomes more and more estranged from the natural environment, we are being driven to believe that we no longer need to hunt for our food or to hunt at all. There is more and more pressure being put on hunters through the medium of social media platforms telling us that hunters are cruel people who lack compassion and empathy for the animals that they kill. It can be very difficult to ratify our decision to be a hunter in the face of so much external pressure designed to engender guilt. Those of an anti-hunting nature may like to portray hunting as being a brutal and negative expression of mankind, however, hunting is a part of who we are.

More than this, hunting has historically defined us as men. A successful man was one who could provide food for his family and tribe. Hunting was a rite of passage, a successful hunt tangible proof that a boy had reached manhood and was now a functioning and productive member of his cultural unit. Hunting tied us to the land, we were grateful for the gifts given, the sustenance we received from the natural world that fed us and our children. Once upon a time there was no guilt assigned to the hunt, once upon a time a man defined his worth by how well his people ate.

While significant changes in the nature of today’s modern society have altered the way hunting is viewed, I believe that those who enjoy hunting are not anachronisms from a now defunct way of life. We are men still connected to the ways of our ancestors, driven to embrace the natural world and accept our part in it. And so we hunt.

Humanity can look at nature and accept that such creatures as cats, sharks, wolves etc. are natural predators. What humanity fails to accept is that we too are natural predators and we share many of the same traits as both predators and omnivores.

There is one major difference between us and other omnivores and predators and that is our great intellect. It is our intellect that has led to our separation from the natural environment and it is this intellect that has also created what might best be described as unnatural guilt. We experience guilt in a way that other animals do not. If a deer was to step on its fawn, the fawn would cry and the mother would feel immediate empathy along with what we might call a natural guilt which acts as a preventative. Animals do feel guilt - just ask your dog who dug that hole in the yard to see for yourself. Humans on the other hand have the capacity to carry guilt beyond that of animals due to intellect. This can be useful but also at times damaging. We can harbour guilt that becomes self -destructive and as a global community, we can simply harbour guilt to the point that we reject our very being and come to despise our own species.

The antithesis of guilt is compassion. As humans we have the ability to experience great love and compassion. We can utilize intellect, empathy, love and compassion to navigate our way through this world. And it is because of these traits that we can become more effective at hunting. Have you ever seen a domestic cat hunt birds or mice? Small cats can be very cruel at times and many of you will have witnessed this. Even though some folk may think hunters are un-evolved by continuing to hunt in this modern age, the opposite can be true in that we can use our intellect and compassion to make us far better hunters than our fellow predators. To become a truly successful hunter, one must be willing to understand and embrace the principles of effective game killing.

Effective game killing is based on empathy. We wish to hunt and utilize the flesh of another animal. Empathy drives us to find optimal and what we call more humane ways to achieve this. We do not want to live on whey or soy protein because we as hunters accept who we are and we learn to accept that we too will pass from our flesh one day. We want to hunt because it feels right. The feeling can at times physically burn in our heart and the area of our solar plexus. It is natural and healthy. In fact as hunters, we can become more infinitely attuned to our natural place within the universe. This connection can be far deeper than simply listening to Native American music on Youtube while burning sage. It can take us deeper than the ramblings of a church minister or monk - regardless of the fact that any of these practices can be of great benefit to us for our own personal reasons.

When we hunt, we face and accept who we are while at the same time feeling a deep connection to the land and animals of our world. It is a direct experience; we are engaged in such a way that cannot be put into words. Hunting is not for everybody - we are all unique and this is especially important to recognize now that the population of our planet is so high. But for those who do feel the calling, it is one that cannot easily be resisted. Those of us, who do hunt, find we are at our best when we are constantly honing and refining our skills. This very process defines both the hunter and warrior protector.

In addition to matters of compassion, fast and humane game killing directly benefits the hunter. A fast kill allows us to easily locate and retrieve game. A slow kill may allow game to escape to such an extent that by the time we find the carcass, the meat may be spoiled. Without the aid of a dog, we may lose the animal altogether. In mountainous terrain, the animal may run from the ledge it was standing on when the shot was taken, only to fall into a ravine without any hope of retrieval.

The information ahead will help you to become a better hunter. We will start with a brief history of game killing and then move on to the subjects of how bullets kill; what fast killing actually means and then we will look at shot placement. The discussion will then go into more technical detail with regards to how the shape of a bullet tip (meplat) affects terminal performance.

A brief History

All though studies in terminal ballistics may appear to be a relatively new field of research; it is as old as man himself. One of the first major technological breakthroughs in arms was the invention of the bow and arrow. Early bow hunters took effective game killing very seriously. The method in which the arrow killed was through its blades which severed arteries, causing death via blood loss. Whether using a spear or bow, hunters understood that wide blades resulted in fast bleeding. On the other hand, if a blade was too wide and heavy, it would upset the aerodynamic performance of both spear and arrow. Penetration might also be limited. With time and experience, hunters arrived at an ideal blade size to balance these factors.

On average, the primitive bows of the world had a draw weight of about 40lb which by today’s standards would be considered rather light. The bow was of course also highly valued in warfare. War drove bowyers of the day to develop ever more powerful bows to meet battlefield needs. As soldiers adopted heavier armour and greater formations, the power of the bow increased to draw weights of between 80lb and 120lb and in extreme cases, up to as much as 200lb. By the middle ages, two distinct types of arrow were in use, a very heavy armour piecing arrow and a much lighter flight arrow for long range volley fire.

As the bow became a more effective battle weapon, it also became a much more effective game killing weapon. European hunters discovered that by using a powerful bow, it was possible to achieve a complete through and through passage of the arrow on game, resulting in faster, free bleeding. Although death still took several minutes, killing was potentially faster than a shot which resulted in only partial penetration or complete penetration but with the arrow remaining lodged in the animal. The complete pass through of the arrow also encouraged the generation of a blood trail for the hunter to follow. It has been said that it is from these historical experiences that modern European hunters prefer rifle ammunition that completely penetrates and exits game.

Two holes as a means to drain a vessel is a most basic principle of physics. Today, this principle is employed in the design of all fuel systems and can be replicated by trying to empty the liquid contents of a tin or drum, first with only one hole, then with an opposing breather hole. However, it is important that we keep these matters in perspective. Most blood loss from a hunting wound occurs internally. That is to say, an exit wound will not always result in a ‘follow the dotted (or spattered) line’ blood trail. Instead, gravity will generally cause a greater part of the blood content of an animal to fall to the bottom of the chest. An exit wound may help to encourage both free bleeding and help to create a blood trail, but an exit wound cannot be classed as a primary mechanism of fast killing.

In addition to this, there is a vast difference in the rate of bleeding between that produced by a 28mm diameter broadhead and an internal wound of up to 75mm or larger generated by the hydraulic force of a high velocity rifle bullet. Getting back to our history, I would suggest that the main point to consider here without overcomplicating this subject is that a staunched wound (arrow lodged in place) produced a potentially slower bleeding wound than a complete pass through.

Black powder muskets first appeared during the 15th century and gradually superseded the longbow. As with the blades of a broadhead, the diameter of an internal wound was directly proportionate to the diameter of the ball. Therefore, the musket was most effective when loaded with very wide balls. But once again, compromises had to be made. A soldier could only carry so much weight. The smaller the ball, the more ammunition each soldier could carry.

Picture: A client of mine shot this wild goat with a 50/70 rifle. The bullet impacted the shoulder and exited the paunch. The conical non-expanding projectile produced a limited wounding effect, saved only by its diameter.

A later invention was rifling within the barrel to impart a spin on the projectile for greater flight stability. Rifling not only added accuracy to the ball but allowed for the development of cylindrical shaped round nosed bullets. The black powder rifle reached its zenith with the breech loading .44 and .45 calibre rifles of the early to mid 1800’s. These bore sizes achieved the ultimate balance of killing power versus trajectory versus obtainable velocity.

Throughout the black powder era, muzzle velocities were slow by today’s standard. A .58” (.575” / 14.6mm) non-expanding ball or conical projectile leaving the muzzle of a rifle at about 1200fps and impacting at around 1000fps produced very little hydraulic force. Secondary missile effects (i.e. the effects of broken bone fragments) notwithstanding, internal wounds (permanent wound cavities) were generally no more than 25% larger than the diameter of the bullet.

Note: From here on, I have simplified the history. I have left out matters of military development including observations and exploitation of tumbling bullets among various nations. Those wanting to learn about military development and evidence based wound photos can find this in my book, Small Arms Wound Ballistics.

With the advent of smokeless powder (1886) came much higher velocities. With this major increase in energy, both bullet diameter and bullet weight had to be reduced in order to minimize recoil. The first smokeless cartridge projectiles featured round nosed bullets with a gilding metal jacket to minimize the fouling that would otherwise occur if traditional lead projectiles were fired at high velocity.

The next major step forwards was the introduction of pointed bullets to reduce aerodynamic drag. These first appeared towards the turn of the 19th century. Prior to the development of rifling, it was impossible to propel a bullet point first with so much weight toward the rear of the projectile. The next advancement in projectile design came about via the development of the tapered tail bullet now known as the boat tail. A boat tail bullet helped decrease drag while moving the centre of gravity back towards the centre of the projectile. This design helped to stabilize projectiles in flight out to subsonic ranges.

The sporting cartridge benefited greatly from military developments; however a departure in the design of hunting versus military ammunition occurred due to the fact that military convention dictated that full metal jacket bullets must be used in war to minimize excessive cruelty to soldiers.

In contrast, by leaving the tip of a hunting bullet exposed, a high velocity bullet produced rapid expansion and most importantly of all – hydraulic force, resulting in very large and fast bleeding wounds.

A secondary benefit of the expanding bullet was that after developing its frontal area, the weight and centre of gravity of the projectile could potentially shift forward, aiding stability during penetration. Having said this, flat or round nosed expanding bullets generally showed greater inherent stability than hollow or soft pointed bullets when used on large game.

Some interesting Norma history

The Norma ammunition company was founded in 1902 with its first factory built in 1911. Norma was at this time engaged in the production of 6.5x55 military ammunition. During the following decades, Norma took every advantage of emerging technologies. The Nickel jacket 8mm 198 grain BTHP was an extremely violent, fast killing projectile. Later designs such as the Alaska, Vulkan and Oryx hunting projectiles employed a stable weight forward bias for deep penetration while the wide frontal areas also helped to enhance both physical and nervous trauma.

Comment from Robert, Norma Precision: For those looking into the history of Norma, I can recommend the Reloading Manual or the book by the famous Nils Kvale "Kulor, Krut och Älgar" who was instrumental in bringing Norma ammunition to a global cadre of hunters and shooters. As for the trajectory of Norma's product development, there are great resources here at Norma Academy that are continuously expanded upon.

How bullets kill

A projectile kills by causing either one or a combination of the following:

1. Blood loss.

2. Damage to the central nervous system (CNS).

3. Destruction of vital tissue and organs.

4. Septicaemia or asphyxiation.

Each causing the effect that life can no longer be sustained. For hunting purposes, the primary task of the projectile is to provide a fast, humane kill. This minimizes suffering to the animal and simplifies location of the carcass. Destruction of the major nervous centres such as the brain or forwards portion of the spine cause the fastest killing but such targets are often difficult to hit. The most reliable method of killing when using a firearm is via rapid blood loss. Blood loss can be categorized as either fast bleeding or slow bleeding. Fast bleeding refers to the destruction of the major arteries of the chest or neck - resulting in a fast kill. Slow bleeding refers to the muscles and arteries which feed the muscles. When slow bleeding areas are destroyed, the result is a slow kill.

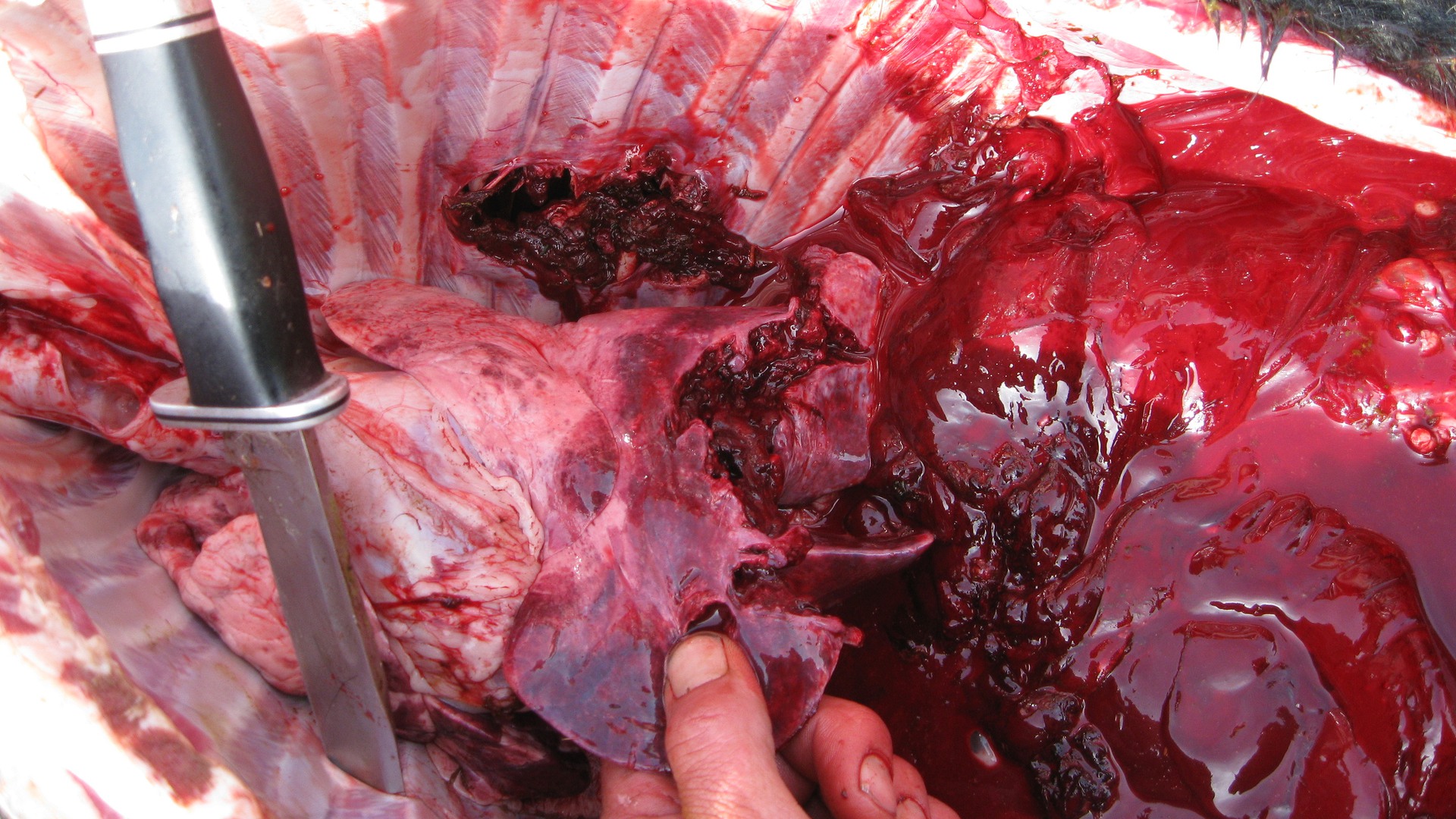

Picture: Fast bleeding. Note the clotted blood (right) as a result of a large lung wound. Note also that the wound through the chest wall and lungs is disproportionate to the size of an expanded (in this case .308) bullet.

When a projectile destroys vital organs such as the lungs, liver or heart, death occurs in the first instance via blood loss, not through the destruction of the organ itself. This is simply because these organs are major carriers of blood through the body and CNS (i.e. oxygen to the brain), therefore kills are relatively fast. Having said this, organ failure does obviously result in death, whether as a primary or secondary factor. Slow kills can also be caused by asphyxiation as a result of minor wounding to the lungs or neck. Gut shots cause a slow death through infection (septicaemia) along with the introduction of digestive acids into the bloodstream and any surrounding damaged organs. A commonly used term for death from gut shots is ‘blood poisoning’ which although gives little away in its description, does at least partially indicate that gut shots do not produce an immediate kills. Put simply, a gut shot can cause immense suffering.

Mechanisms

The modern high power hunting cartridge generally relies on high velocity combined with expanding type projectiles. As the projectile strikes flesh, the projectile changes its form, causing displacement of tissue through both physical contact as well as pressure. The projectile transfers its kinetic energy to the surrounding tissue causing acceleration of fluid particles in and around its path. This creates an explosive temporary wound channel that subsides to a wound channel which may be far greater than the diameter of the projectile. The temporary wound channel reaches its maximum size within one millisecond, collapsing to its final size within several milliseconds.

In both military and sporting applications these two types of wound damage are referred to as the temporary wound channel and permanent wound channel, both having the effect of causing blood loss, organ and or CNS damage depending on shot placement.

At this point I would urge readers to discard temporary versus permanent wound channel terminology. Such terms are simply unhelpful. A hunter does not walk up to a kill and state, “boy, you should have seen that temporary wound channel, lucky I didn’t blink”. No human has the ability to see such things frame by frame and therefore, a wise man should drop such intellectual pontification. There are far more important factors to focus on.

Fast Killing

As already discussed, fast killing is an important factor for two reasons, compassion and game retrieval. If shot placement is poor or should the wrong cartridge or bullet design be selected, game may run several hundred metres before expiring. In other instances, death may take several days. In order to get the best results it is important to understand the mechanisms of fast killing.

A common misconception when witnessing game collapse seemingly instantaneously is that the force of the projectile has physically knocked the animal to the ground. Many hunters would consider this to be an instant kill. However; Newton’s law suggests that for every force there is an equal and opposite force. To this end the force of the bullet impacting game is no greater than the recoil of the rifle. So what causes the instant collapse or poleaxe as it is sometimes caused? Instant collapse occurs when the central nervous system (CNS) is damaged or electrically disrupted as a result of one of two mechanisms - either direct or indirect contact. A bullet that does not directly strike the CNS will not cause instant death.

- Direct contact of the CNS

This refers to a bullet directly striking and destroying one of the major nerve centres, including the thoracic and cervical vertebrae, the brain or the autonomic plexus (nerve ganglia in upper thoracic cavity). Regardless of velocity, if the CNS is destroyed, this will result in instant death.

- Indirect contact of the CNS

This refers to the effects of a high velocity bullet imparting its energy, creating a hydrostatic shock wave. In terminal ballistics, the terms hydraulic shock and hydrostatic shock both refer to kinetic energy transferred to flesh, however, each term describes different results.

- Hydrostatic shock

This is a now very old term coined by U.S gun writers during the 1950’s. The word hydro refers to water while the word static is used to imply electrical interference (not static electricity). This term refers to the effect of concussive pressure waves travelling through flesh, interrupting distant nerve centres. Be aware that the terms hydraulic and hydrostatic shock are quite often misused by both hunters and professionals - including ballisticians working for bullet making companies.

When game animals drop instantly and in the absence of CNS destruction (e.g. a centre chest hit), it is generally due to hydrostatic shock. A high velocity bullet that is well matched in weight and construction to the game body weight, imparts over half of its energy within the first 2cm of penetration, creating a concussive wave. This concussive shock wave travels outwards via the rib cage until it reaches the nerves of spine, disrupting the electrical activity of the brain (CNS). The result is an immediate loss of consciousness. A projectile which creates a large internal wound will drain all of the body’s blood within several seconds. The loss of blood and damage to vital organs cause death to the animal before it has the chance to regain consciousness. Hydrostatic shock causes the ’knocking over’ illusion while blood loss during coma reinforces this illusion to the point that we believe we have witnessed an instant kill. More careful examination may show that our shot caused coma, followed by blood loss, followed by death.

The hydrostatic shock created by a hunting bullet is identical in action to when a boxer is struck on the jaw by his opponent, disrupting the functions of the brain with a resulting loss of consciousness. The single most important factor we need to understand about hydrostatic shock, is that although we may be able to encourage this phenomenon, we should never expect it. Nor should we ever rely on this as a mechanism of killing. The subject of hydrostatic shock is provided here simply to help hunters understand terminal ballistics effects.

Our primary focus should always be toward creating wide internal wounds that cause fast bleeding and therefore fast killing. This is achieved via mechanical and hydraulic force.

So far, I have discussed death as a result of a direct CNS strike versus coma caused by nervous shut down. Neither of these factors have any bearing on internal wounding. We must now therefore investigate how internal wounds are produced.

- Hydraulic force (also called hydraulic shock)

When a high velocity bullet strikes a water filled target, energy is released into the target in the form of hydraulic force. Various factors such as velocity, bullet shape, weight and construction each have an effect on how much force is transferred to the target. A high level of hydraulic force will create a wide internal wound.

- Mechanical action or force

A term of my own invention, mechanical action involves the force of bullet materials acting directly on tissues so as to cause destruction. Provided the bullet has sufficient velocity (kinetic energy) to penetrate and or mushroom (or break up), the bullet will cut and destroy tissues within its path.

Wound factors

- Velocity

Velocity has a great effect on mechanical and hydraulic wounding factors and is a key element of hydrostatic shock. Put simply, the higher the impact velocity, the greater the kinetic energy. As a basic example, the Norma 7x64 Tipstrike has a bullet diameter of 7mm. A recovered bullet (from game) may be around 14mm in diameter indicating its theoretical mechanical wound potential (i.e. a wound 14mm in diameter). Yet due to hydraulic force, an internal (permanent) wound through the lungs may be over 80mm in diameter. In other words, hydraulic force as a result of high velocity can cause extremely fast kills.

Hydrostatic shock is also enhanced via high velocities. In bore sizes from .243” up to .338”, nervous shut down begins to become evident at impact velocities over 2600fps. Of the thousands of medium game animals harvested during my research, 2600fps has been the most common cut off point.

High velocity is not however a sole factor to be worshipped and held above other factors. For example, if velocity is increased too far without increasing bullet weight, the surface tension of water within the animal can cause so much resistance as to overcome the energy of the bullet. Ultra-high impact velocities can therefore lead to shallow penetration and without any nervous reaction from the animal.

One factor to be very careful of with ultra-high velocity conditions is to not blame a delayed kill exclusively on ‘bullet blow up’. For example, a 140gr 7mm bullet striking at an impact velocity of about 3200fps may show some signs of wide entry wounding and surface bullet blow up (or possibly blow back). But we must investigate further if we are to truly understand factors at play. In this instance, once the animal is recovered, it is important to study the vital organs and determine whether they were actually destroyed. If the vitals were destroyed, we can then conclude that the bullet worked well (even if in a less than desirable manner) but without evidence of hydrostatic shock.

Frangible bullets or more correctly any bullet capable of shedding up to or more than 50% of its weight within game may produce immediate coma on medium game at impact velocities lower than 2600fps. Having said this, the bullet must generally have a very thin jacket and contain a great deal of weight (relatively heavy for calibre) in order for this to occur. When a frangible bullet strikes at low velocities, instant coma may occur simply due to the massive amount of energy imparted at the moment of contact. In other instances, coma can follow very shortly after impact due to the severity of both nerve and tissue wounding. Small fragments may also directly strike the CNS. The now obsolete Norma 8mm 198 grain Hollow point is an example of this type of bullet. This was a fully frangible bullet, producing excellent performance on medium game. But after showing limited performance on large bodied game, its strengths were forgotten and it eventually lost favor among hunters.

Picture: The Norma bullet that started it all for me as a very young boy. After my father retrieved a 198gr Norma HPBT for me, I was hooked on the subject of firearms and ballistics.

Although velocity is a key element of Hydrostatic shock it is not the only factor. Hydrostatic shock may also occur on medium game at impact velocities below 2600fps via an increase in bullet diameter. When using a medium (.358”) bore or larger, hydrostatic shock may sometimes occur on medium game species (e.g. Red deer or boar) at impact velocities as low as 2200fps. But in order for this to occur, the bullet must be of an appropriately soft construction. The Norma 9.3x62, 232 grain Vulkan is a good example of a fast expanding medium bore load. The muzzle velocity for this load is rated at 2625fps, the Vulkan remaining above 2200fps out to a distance of around 130 metres. In older rifles with worn throats generating lower muzzle velocities of around 2550fps, the Vulkan breaks 2200fps at around 110 metres. Inside these ranges, provided the hunter employs sound shot placement, it is possible to encourage nervous shut down on medium game.

When studying hydrostatic shock on bovines, I have discovered that reactions may occur at impact velocities of 2600fps provided the projectile is suitably heavy and of a sound construction. In some instances, the bovine may regain consciousness and attempt to rise. But in doing so, blood loss is increased and death follows within seconds. More consistent results are achieved at impact velocities of around 2900fps and higher, using bullets weighing at least 300 grains.

- Bullet weight versus game weights

In order to achieve acceptable penetration, a bullet must have sufficient weight for the intended game animal species. Furthermore, if the bullet is too light for the intended game species, it may lack enough kinetic energy to generate a wide wound via either mechanical or hydraulic force.

If a bullet is too light, it may meet far too much resistance on impact. This is a common occurrence when using ultra velocity .22 centrefires on various medium game species. If the bullet is driven extremely fast, it may in theory have sufficient kinetic energy but in reality it may lack sufficient weight to deliver this energy within the target. Any increase in velocity will by the same token cause an increase in target resistance (surface water tension).

Less obvious, is the result of using a bullet weight that is too heavy for the intended game animal. If the projectile contains too much momentum, the bullet may fail to meet enough resistance to impart energy where it is required. The bullet may fail to produce nervous trauma and create only limited internal trauma. An example of this may occur when using a stout 9.3 calibre 286 grain bullet on lighter bodied medium game. Finding the right balance between bullet weight versus game weights can create many difficulties for the hunter when selecting an appropriate cartridge and bullet as a certain level of momentum is required if the bullet is expected to penetrate into vitals from any angle or give satisfactory performance on a variety of game body weights.

- Projectile construction

Of the three elements (weight, velocity, construction) it is bullet construction that has a pronounced effect on overall hunting performance. The transfer of mechanical force, hydraulic force and hydrostatic shock are each influenced by the construction of the projectile.

Key points worth considering:

- A homogenous copper bullet will typically retain close to 100% of its weight after striking flesh. Such a bullet is generally described as being tough or stout. It is important to understand that although Norma can produce a copper bullet in such a way that it readily expands at low impact velocities, Norma cannot alter physics. Without any major weight shedding action (this requires more than mere petal shedding), hydraulic force begins to diminish, starting at 2600fps, becoming more evident at 2400fps with a major reduction in performance at 2200fps. Throughout these impact velocities, wound channels steadily become proportionate to the expanded calibre of the bullet though some evidence of hydraulic force will remain at 2200fps. These bullets are most useful at close to moderate ranges where impact velocities remain above 2600fps and are especially useful for anchoring large or tough animals. At longer ranges (where velocities drop below 2400fps) or when used in low velocity cartridges, kills may be somewhat delayed. Expansion may also be delayed should the bullet meet only very light resistance. Shot placement is therefore of great importance, especially at low impact velocities. Due to the lighter weight of copper compared to lead, homogenous copper bullets are generally much longer than lead core bullets of the same weight. In order to avoid poor accuracy due to insufficient barrel twist rates, light bullet weights are employed as a means to reduce copper bullet lengths. This does not reduce penetration.

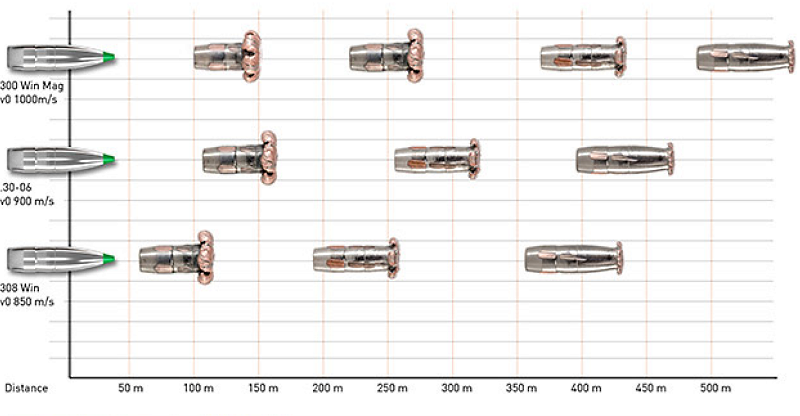

It is rare to see this level of transparency from a company these days. But in the above graph created by Norma ballisticans, we can see the strengths and limitations of the Ecostrike projectile.

- Norma have produced bonded ammunition in one form or another for more than two decades. A bonded bullet such as the Bondstrike, Oryx, A-Frame or Woodleigh will typically retain about 75% of its weight after penetrating flesh. These projectiles are designed to strike an optimum balance between wounding and penetration. Any change in form (loss of the bullet shank form during penetration) or weight shedding, greatly aids the energy dumping process. Many such bullets are specifically designed to produce excellent mushrooming at impact velocities of between 2400 and 2200fps in order to suit various African cartridge muzzle velocities and expected impact velocities. But in order to perform optimally, the bullet must be suited to the intended game. To help hunters, Norma offer suggested game species for each of their loadings (see cartridge details on Norma website). As with copper bullets, a bonded bullet can be designed to expand at fairly low impact velocities although there are limitations to how far this can be taken. Expansion at 2400fps may for example be delayed if the bullet meets insufficient resistance. At impact velocities of 2200fps and in the absence of major hydraulic force or bullet weight loss, wounding becomes more proportionate to the expanded calibre of the bullet. At impact velocities of around 2000fps (older / slower African cartridge designs) a bonded bullet will normally retain 100% weight and in the absence of either high velocity or weight loss (mechanical action) wounding effects are limited. Hunters using older slower cartridges should therefore aim for heavy muscle and bone in order to enhance hydraulic energy transfer. Bonded ammunition works exceptionally well on large and or tough species of game such as the African Oryx, from which Norma have named their primary bonded bullet design. The Bondstrike is somewhat different to the Oryx in that it is designed to fully expand at low impact velocities. But without any weight shedding action at speeds of 1800fps wounds are not widely diffused. Shot placement is therefore important at extended ranges yet wind drift can ruin such efforts. For the sake of humane killing, those who wish to use the Bondstrike below an impact velocity of 2200fps are advised to use it on tougher species of medium game and only in very low wind conditions and to not push this projectile past an impact velocity of 1800fps.

Although bonded bullets can be designed to expand at low speeds, one should never push a bonded bullet too far, simply because physics dictate that in the absence of hydraulic force, wounds (as per the above) will be proportionate to the expanded caliber of the bullet. If shot placement is less than perfect, kills may be extremely slow.

- Conventional lead core bullets such as the Norma pointed soft point, Alaska, Vulkan and Tipstrike retain on average around 50% weight after penetrating flesh, though weight loss can be higher under certain conditions. Due to the fact that these bullets have a high mechanical action in the absence of high velocity (hydraulic force), good wounding effects can be seen at low impact velocities of approximately 1800fps. In some situations (large / heavy game), a conventional bullet may not be a good choice. But there are many situations where a conventional bullet can prove superior to new technologies. Examples include hunting lighter bodied game or especially when used in older / slower cartridge designs. High weight shedding is also imperative for long range hunting.

The excellent 7mm 170 grain Vulkan (left) dumps a vast amount of energy. Yet an even greater energy dump can be achieved with the Tipstrike which can also be used out to extended ranges.

It is important that the hunter understands bullet construction so that he or she can obtain optimum performance from his ammunition. Using the .30-06 as an example, the stout 180 grain bonded Oryx is an excellent choice for very large bodied deer. However by the same token, this bullet can produce extremely poor results on Roe and Fallow deer. At certain times of the year, the 180 grain Oryx can also prove too stout for Red deer, more so when aiming behind the shoulder. The Oryx will without a doubt kill any of these deer species, but due to the fact that expansion is delayed, the energy exchange (hydraulic force) may be poor. The Oryx is therefore reliant on its ability to produce a mechanical shearing action along with limited hydraulic force. If the bullet has only partially mushroomed during penetration, the wound will (as those who have tried this will agree), be only around 15 to 20mm in diameter. By simply changing the construction of the bullet to that of the 170 grain Tip Strike or 180 grain Vulkan, the wound will be very large. Bullet construction is therefore more influential than weight.

There are however times when a tough bullet may be required for medium game. The .243 is for example well served with a bonded bullet if used on wild boar. By the same token, the .22-250 (where legally allowed) loaded with an Oryx bullet can be put to good use on pigs weighing up to around 60kg. But it is also important to understand that very small bore cartridges achieve large wounds via either speed or in the absence of speed, some measure of bullet weight loss. It is therefore unwise to use a bonded bullet in the .243 at extended ranges where energy is low.

As a general rule, one can forego bullet construction in exchange for weight. In other words, the heavier the bullet, the less concern there is for tough bullet construction. It is for this reason that the Alaska has remained popular for such a very long time. Unfortunately, many hunters do not understand these finer attributes. Such misunderstandings have placed considerable demands on ammunition manufacturers who are expected to make bullets that are both extremely tough, yet are somehow also expected to generate optimum wounding at very low impact velocities.

There are however some situations for which there may be no choice but to use a stout bullet on lightly built game. In some countries, hunters are required by law to use solid copper bullets. If using a copper bullet, the hunter must focus his attention on shot placement and the production of hydraulic force (high velocity).

Heavy and stoutly constructed bullets are at their very best when used on large or tough bodied game animals. Norma furnish many such loads suitable for hunting Moose and large African game.

Solid bullets are used for hunting large and potentially dangerous game with an emphasis toward deep penetration from all angles. The wound potential of a non-expanding bullet is limited, but can be enhanced somewhat via the shape of the bullet tip. Norma currently offer a range of solid bullet designs, each featuring flat points in order to promote both hydraulic force while maintaining optimum stability during penetration. Generally speaking, the hydraulic force of a flat point solid is most pronounced at impact velocities above 2600fps, however disproportionate to calibre wounding is still vivid at impact velocities of 2400fps. The wound may be up to four or even six times larger than the bullet diameter at this impact velocity. Obviously, in order to exploit this performance, the hunter needs to get close to his quarry, using these impact velocity parameters to one’s advantage. Further wounding effects can be obtained by aiming at major bones, the result being secondary missile effects, causing increased internal wounding. The destruction of bone and locomotive tissue also helps to promote incapacitation.

The Norma 285 grain Oryx produces an excellent balance of wide wounding versus deep penetration on large game.

Long range hunters must understand that in order to create a wide wound (fast killing) at low impact velocities, the bullet must be of soft construction and must shed weight. At low impact velocities, projectiles produce very little hydraulic force; therefore mechanical force (bullet weight shedding) must be employed in the absence of this action. More details on this subject can be found within my book, The Practical Guide To Long Range Hunting Cartridges.

- Bullet diameter and frontal area

The fourth factor of wounding is bullet diameter and frontal area. Put simply, the wider the calibre, the less need there is for high velocity to initiate hydraulic and or hydrostatic force.

Wide and short bullets will by their very nature dump energy faster than long and narrow projectiles. There are however limitations to these equations. A wide bullet cannot for example overcome any issues relating to bullet construction. If the jacket of a medium or large bore bullet has been designed for large game, such as the 9.3 285 grain Oryx, chances are that kills on light or lean game may be delayed. In this example, a better choice would be either the 285 grain plastic point or the 232 grain Vulkan. A key factor that needs to be understood is that if you choose a medium bore for an increase in performance over a mild cartridge such as the .308, you must still match bullet construction to the job at hand. If you choose a very stout and heavy bullet and use this on (as an example) boar in forest / swamp conditions, anything less than a large fully mature boar may run a very long way before bleeding out.

The shape of the bullet tip also effects terminal performance.

Match bullets (without a plastic tip) tend to have very small hollow points which generally produce poor expansion and therefore narrow wounding.

Pointed soft point hunting bullets generally feature a suitable cross sectional area to ensure good expansion down to impact velocities of around 1800fps without sacrificing aerodynamic performance.

As previously discussed, provided velocity is relatively high, a flat point non-expanding bullet can generate considerable hydraulic force. If the projectile is long for calibre (a high sectional density), the wide wound may continue to a very great depth. The excellent terminal performance of a flat point can also be exploited within expanding bullet designs. The Norma Vulkan is particularly interesting in this regard as is the Alaska round nose bullet. Both meet a great deal of resistance at the moment of impact, dumping energy quickly. In fact it is possible to observe the difference in energy transfer at the very surface level of a test medium, particularly from a Vulkan bullet which under the right conditions will produce small volcano like protrusions upon the surface of the medium.

The limiting factor of a flat or round nosed bullet is a reduction in aerodynamic performance. As speed falls away, the bullet is not only affected by drop, but also suffers a reduction in energy along with high wind drift. Many years ago, I built an 8mm-06, specifically so that I could drive the 196 grain Norma Vulkan bullet at very high speeds. As a young man, I had hoped that by increasing speed (in comparison to the 8x57 cartridge), I could exploit the wonderful performance of the Vulkan for hunting Red deer in both forest and more open country. The 8mm-06 produced exceptionally fast kills but my expectations were too high for longer ranges. Although the Vulkan showed excellent wounding characteristics down to 1800fps, it displayed significant wind drift when used in the high country. I managed to take several one kill shots out to ranges of around 400 metres, yet wind drift was around 60cm. The trouble was, I was using this bullet in a manner for which it was never designed.

Hollow point hunting bullets have much wider hollow cavities than match bullets, offering a relatively wide yet weak surface area, ideal for rapid expansion. Norma’s obsolete 8mm hollow point was a classic example of this. The one drawback of this design was the reduction in BC as a result of the gaping wide tip.

A plastic tip can enhance performance in three ways. Firstly, plastic is somewhat more resistant (but not immune) to deformation than lead. This is most useful in high powered rifles where ammunition stacked in a magazine is thrown about during recoil. A second benefit is that plastic tips can help to enhance aerodynamic performance (BC). The third major benefit is that by utilizing a plastic tip, the bullet maker can employ a very wide hollow point, thereby enhancing terminal performance without any loss in aerodynamic performance. The Norma Tip Strike bullets are an ideal example of this. The Tip strike is not only fast expanding, but thanks to a relatively high BC, it retains excellent downrange energy. For those who do not know where to start, my experience over many years has lead me to conclude that a fast expanding 160 grain bullet is an ideal starting point when selecting a cartridge for all around use (Roe to Red deer / short to longer ranges). This is most perfectly expressed in Norma’s 7x64 and 7mm Remington loads featuring the 160 grain Tip Strike and further echoed in the .30 calibre 170 grain offerings.

It should be noted that the subject of bullet diameter and frontal area are directly related to bullet construction and other factors. Each are interrelated with regards to terminal performance. For example, some Norma loads designed for large bodied game can work well on light or lean bodied game, purely as a result of having a flat bullet tip.

Conclusion

The subject of fast killing can be used to measure cartridge or bullet performance. It must however be understood that the word effective by definition in this instance, describes the ability of the cartridge to achieve broad (and acceptably deep) wounding and has no maximum limit to power. An efficient cartridge on the other hand describes the ability of the cartridge to kill using the minimum necessary power. I do not believe that efficiency should ever be put ahead of effectiveness.

- A wide wound causes a fast kill. Those who like to complain about meat damage should perhaps take a moment to think about this.

- At high impact velocities, the hunter can rely on hydraulic force to generate wide, disproportionate to expanded calibre wounds.

- At high impact velocities, hydrostatic shock may also be evident. This can be encouraged, but it cannot be relied upon. Factors such as bullet weight, game weights, shot placement and nervous conditions (calm animal versus adrenalized animal) each influence the effect.

- Hydraulic force diminishes as impact velocities are reduced (especially below 2200fps). If the bullet is too tough for the job at hand, wounds will be proportionate to the expanded calibre of the bullet and kills may be slow.

- At lower impact velocities, the mechanical action of bullet mass and weight shedding can be used to regain disproportionate to calibre wounding.

- Norma produce a wide range of hunting bullets suitable for a variety of applications. It is important that you understand the strengths and limitations of these designs so that you have realistic expectations

- Non-expanding solids are designed for use on large heavy game. The flat point design utilized by Norma helps to promote hydraulic force. But in order to enhance this effect, the hunter should get close and aim to break major bones.

- Homogenous copper bullets (Ecostrike) produced by Norma will retain 100% weight and produce excellent penetration and internal wounding at high impact velocities. These bullets are useful for hunting large and tough game at close to moderate ranges. Game reactions may however be delayed at impact velocities below 2600fps and hydraulic force will also gradually diminish below this speed. It is important to match the weight of these bullets to your intended game. For light to medium weight game, utilize light weight bullets. Selective shot placement, aiming to break shoulder bones, can also greatly aid wounding at longer distances. On large game, utilize the recommended bullet weights and aim to break major bones.

- Bonded bullets (Bondstrike /Oryx / A-Frame) shed around 25% weight during penetration. These bullets are designed for tough or large and heavy bodied game. Bonding helps to enhance penetration while the vivid change in form (compared to copper bullets) along with a small amount of weight shedding helps to promote wounding. Again, one must match bullet weights to game weights in order to ensure maximum energy transfer. If the bullet is correctly matched to game, wounding will be adequate to impact velocities of around 2200fps, thought the Bondstrike can be used to longer distances under appropriate conditions. If the bullet is too heavy or too stout, wounds may be narrow at impact velocities at or below 2400fps. Once again, aiming to strike major muscle groups and bone can help to enhance wounding effects at low impact velocities.

- Jacketed lead core bullets such as the Alaska, Vulkan and Tipstrike shed up to 50% of their weight, allowing these bullets to achieve wide wounding via mechanical action at impact velocities as low as 1800fps. The Alaska and Vulkan feature round and flat pointed tips in order to enhance energy transfer. The Norma Plastic Tip employs both a wide frontal area and massive hollow point behind its tip, producing excellent wounds even though bullet weights may be heavy and impact velocities low. This is an excellent way to obtain consistent performance across a wide range of body weights. The Tipstrike utilizes a weak ogive and high retained velocity (energy) in order to generate extremely broad wounds. Although the Tipstrike is a flat base design, it can be used out to extended ranges.

In order to fully exploit the information within this article, the reader can obtain the muzzle velocities and G1 BC’s for any Norma loading within Norma website product pages. This information can be plugged into an online ballistics calculator in order to determine expected impact velocities at various ranges and therefore expected bullet performance and wounding outcomes. To obtain precise data (especially for longer range shooting), a chronograph can be useful for establishing exact muzzle velocities. In lieu of this, if you have an older (worn) rifle, a rifle of loose chamber dimensions or a rifle that perhaps features a shorter barrel than that used by Norma for testing, remove 70fps from the published muzzle velocity as a very rough guide. As an example of this, at the factory tested muzzle velocity of 2919fps, the 7x64 Norma Tipstrike breaks 1800fps at around 620 metres (roughly 680 yards). If we remove 70fps from this muzzle velocity, the Tipstrike breaks 1800fps at around 594 metres or 650 yards.

No single bullet design can serve all situations. Each bullet design (no matter who the manufacturer) has its strengths and limitations. One of the greatest aspects of educating hunters toward a sound understanding of terminal ballistics combined with realistic expectations is that it allows the ammunition manufacturer to advance product development. Those who for example, complain about ‘bullet blow up’ in situations where the bullet has produced both excellent wounding and adequate penetration, merely add confusion to this subject. The same can be said of those who complain that a retrieved Woodleigh Weldcore or Swift A-Frame has shed weight and has a musket ball shaped appearance rather than a T shaped cross section. If the bullet maker is given no choice but to make all of their bullets extremely tough in order to minimize unwarranted negative feedback (negative marketing), the manufacture will eventually become backed into a corner. The manufacturer will be forced to produce products that meet hunter’s unrealistic expectations, but which may perform poorly in the field. As the saying goes, be careful what you wish for.

The Swift A-Frame (left) versus a prototype bullet design. Although this prototype bullet produced deep penetration, kills were very slow, making it extremely frustrating to use.

Norma want the best for their customers and the very best way to empower customers is via knowledge. The fact that Norma have allowed me to publish the strengths and limitations of their bullet designs as a result of my many years of field research, should at the very least, show the reader how deeply this company is committed to product transparency, game welfare and hunter education.

In part two of this article, we will put this information into use via the study of shot placement.

Text and photo: Nathan Foster

Founder of Terminal Ballistics Research